News

Light-years Ahead

July 29, 2021

Before Buzz and Woody, before Sully and Mike, there was Alvy and Ed, two of the original members of the New York Institute of Technology Computer Graphics Laboratory (CGL). Alvy Ray Smith and Ed Catmull—whose pioneering techniques were born in Gerry House, the “pink building” on the Long Island campus—were among the young computer graphics geniuses who helped make animation what it is today. A long-standing point of pride for New York Tech, their CGL innovations eventually led to the creation of the Pixar powerhouse that forever changed animation.

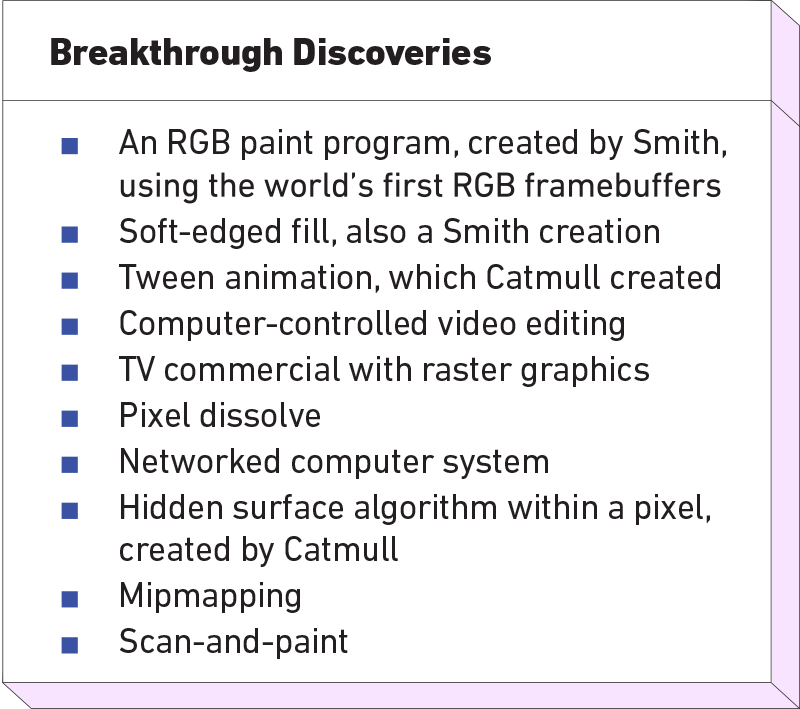

Ed Emshwiller and Alvy Ray Smith at New York Tech circa 1979. Photo courtesy of Alvy Ray Smith

Ed Emshwiller and Alvy Ray Smith at New York Tech circa 1979. Photo courtesy of Alvy Ray SmithIt all began in 1974 with an idea proposed by New York Tech founder Alexander Schure. His dream was to make the first computer-assisted animated movie using off-the-shelf, state-of-the-art minicomputers from Digital Equipment Corporation, known as PDP and VAX computers, which were designed for use in laboratories and research institutions.

Schure enlisted the help of Catmull, a recent graduate of the University of Utah’s advanced computer graphics department. While still a graduate student there, he had discovered how to bring computer-generated graphics to life using texture mapping and bicubic patches and had invented algorithms for spatial anti-aliasing and refining subdivision services. Schure reached out to Catmull, who was working at Applicon in Boston at the time, and lured him to Long Island and the CGL.

Schure soon recruited other talent to join the CGL team. “I met Ed when I found my way to New York Tech. I had already talked my way in with Schure, and when Ed told me what he was doing, I said, ‘You need help, don’t you?’ He said enthusiastically, ‘Yes!’” recalls Smith, and they set forth on their goal to create a completely computer-generated film.

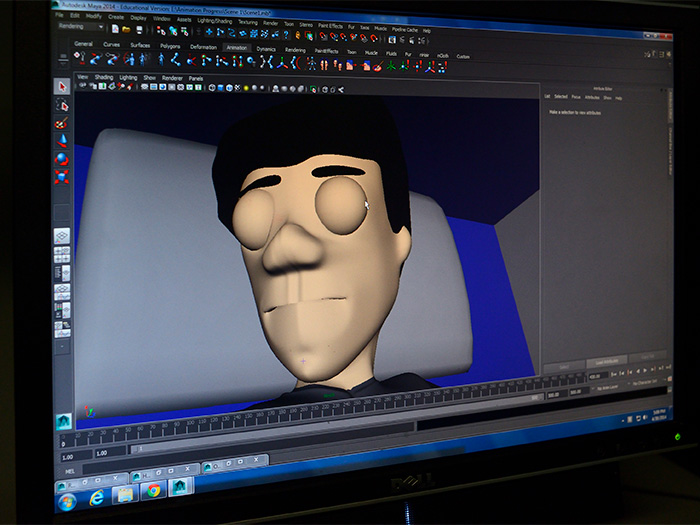

“Almost everything we touched at ‘The Lab,’ as we called it, was a first,” Smith recalled in a 2003 interview with NYIT Magazine.

“We were responsible for the first alpha channel—which means that we added transparency to the basic color pixel,” Smith noted in the same interview. “The list goes on and on. Oh, and it was also the first concerted effort to have artists work with technologists.”

A Collaborative Spirit

Soon they were joined by other tech-minded gurus hungry to do something novel. Together, the group charted new territory, paving the way for an increasing number of computer graphics and animation specialists.

In the computer graphics history book CG 101: A Computer Graphics Industry Reference, CGL alumni Paul Heckbert and Smith recalled the collaborative spirit of New York Tech:

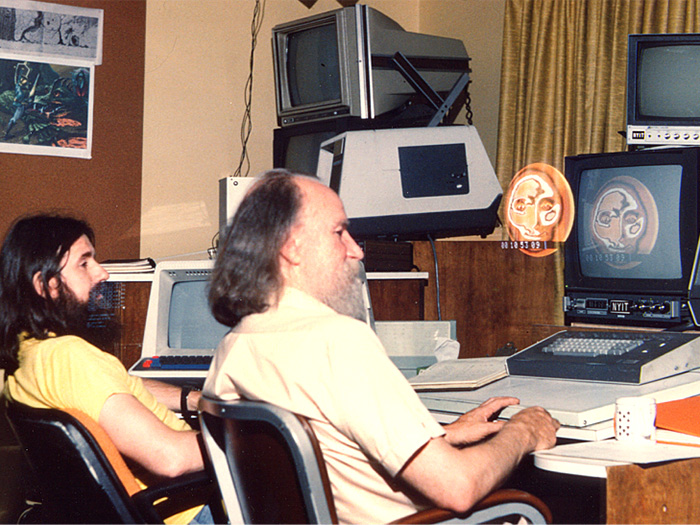

Students in the 3-D motion capture studio on the Long Island campus. Photo by Jason Jones

“The CGL quickly attracted other technology experts and artists, including Christy Barton, Tom Duff, Lance Williams, Fred Parke, Garland Stern, Ralph Guggenheim, Ed Emshwiller, and many others. Throughout the 1970s, the people of the CGL thrived in a pioneering spirit, creating milestones in many areas of graphic software. Many of the firsts that happened at New York Tech were based on the development of the first RGB full-color (24bit) raster graphics.

“The atmosphere at the CGL was also very open, with many invited tours coming through the lab all year-round. Other universities like Cornell, and companies such as Quantel, were among those to visit and take notes about what was being developed. The personnel structure was virtually nonexistent, with never any heavy-handed management from Dr. Catmull. People did what they were best at and helped each other out whenever needed.”

To Infinity and Beyond

As the team worked on projects and developed new techniques, they also hit a few bumps in the road, including the release of Schure’s animated musical comedy, Tubby the Tuba, in 1975. Inspired by his desire to compete with Disney films, Schure wanted to make a movie using computers, but in the end, Tubby the Tuba was made at New York Tech using traditional animation. That actually pleased the CGL designers who sat through the finished film.

Sample of a computer graphic rendering. Photo by Martin Seck Photography

“It was awful, it was terrible, half the audience fell asleep at the screening,” Catmull once recalled. “We walked out of the room thinking, ‘Thank God we didn’t have anything to do with it, that computers were not used for anything in that movie!’”

In 1979, Lance Williams presented another idea for a movie. The CGL group began work on The Works, which centered around a robot, Ipso Facto, and a young female pilot named T-Square. Throughout the development of the film, new computer graphics breakthroughs just kept on coming, and the pink building buzzed with activity and excitement through the mid-1970s and into the early 1980s. In this incubator of innovation, computer graphics wizards honed their craft with the underlying goal of finishing The Works. However, “the roadblock was the technology available. Computers at the time were slow and simply didn’t have the processing power required to create the number of images they needed for a 90-minute film,” according to Film Stories. By the mid-1980s, the film was shelved. Had it been completed as scheduled, it would have been the first CGI movie ever made.

It was only a matter of time until the talent housed in the CGL was tapped to launch new dimensions in animation on a worldwide scale. Catmull and Smith were lured away from the CGL to Lucasfilm Ltd. to head its new computer graphics division. George Lucas, of Star Wars fame, had created the company to launch exciting new endeavors in film graphics. Some of their CGL colleagues left with them or soon afterward, and some joined them in later years.

The Lucasfilm group circa 1984. Photo courtesy of Alvy Ray Smith

The Lucasfilm group circa 1984. Photo courtesy of Alvy Ray SmithAnd while the progress they made at the CGL helped launch their careers, it was just the start of computer animation as we know it today. Smith’s first hand at directing at Lucasfilm was The Adventures of André & Wally B. The 1984 short film introduced filmgoers to computer animation using techniques gestated and born at the CGL. And it was unlike anything anyone had ever seen: motion blur in CG animation; complex 3-D backgrounds featuring lighting and colors using particle systems; manipulatable shapes that could stretch and contract, creating realistic visuals. And despite all this complexity, The Adventures of André & Wally B stunned viewers with its impressive and seamless effects.

“We were responsible for the first alpha channel—which means that we added transparency to the basic color pixel. Oh, and it was also the first concerted effort to have artists work with technologists.”

Alvy Ray Smith

The founding members of the CGL may have left The Works behind on the cutting room floor, but what they began on the New York Tech campus became the seeds of the graphic animations we now take for granted.

When Pixar spun out of Lucasfilm in 1986, it had financial backing from Steve Jobs, and its co-founders were Catmull and Smith. At Pixar, animation was continuously designed, perfected, and reimagined, and in 1995, Toy Story was released. Bringing beloved toys to life, much like they would appear to a young child, the film delighted moviegoers. Audiences wanted more, and they got it. A Bug’s Life, Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, Cars, Up, and Inside Out are among the films created and produced by Pixar by many former members of the CGL.

The developments inside the pink building on the Long Island campus have been featured in countless television shows and movies through the years. Reflection mapping, developed by CGL members Gene Miller, Lance Williams, and Michael Chou, was used to enhance shiny objects in the movies Terminator and The Abyss. Smith’s 24-bit paint program influenced the paint system at Lucasfilm and was used by the artist LeRoy Nieman in 1978 for his interactive painting during Super Bowl XII. And even though The Works was never finished, the film is regarded as an important first in computer animation.

As Buzz says in Toy Story, it was “to infinity and beyond” for New York Tech’s Computer Graphics Lab as the innovation born on the Long Island campus has inspired young and old and will be felt for generations to come.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of New York Institute of Technology Magazine.